The Nabis, an artistic movement dear to Lalou

Lalou Kraffe's work maintains a strong link with the Nabi movement through his search for Total Art, his taste for the poetry of everyday life and the influence of Japonism.

Like the Nabis, she favored the simplification of forms, the intensity of colors and the integration of decorative motifs, while drawing inspiration from Japanese art and the Vienna Secession.

His delicate and meticulous painting extends the Nabi spirit by creating a dialogue between beauty, emotion and contemporary life in each work.

out of stock

The Nabi movement

Break with academic tradition: The Nabis rejected academic painting in favor of a freer and more personal expression, encouraged in particular by the influence of Paul Gauguin.

Symbolism and spirituality : The group, whose name means “prophet” or “inspired,” places spirituality and symbolism at the heart of its artistic approach.

Decorative aesthetics : The Nabis favored refined forms, flat colors, marked contours and a strong decorative dimension, aiming to abolish the boundary between major arts and decorative arts.

Total art and multidisciplinarity : They seek to integrate art into daily life by working on numerous media (painting, tapestry, stained glass, objects, posters, etc.), and defend the idea of a total art.

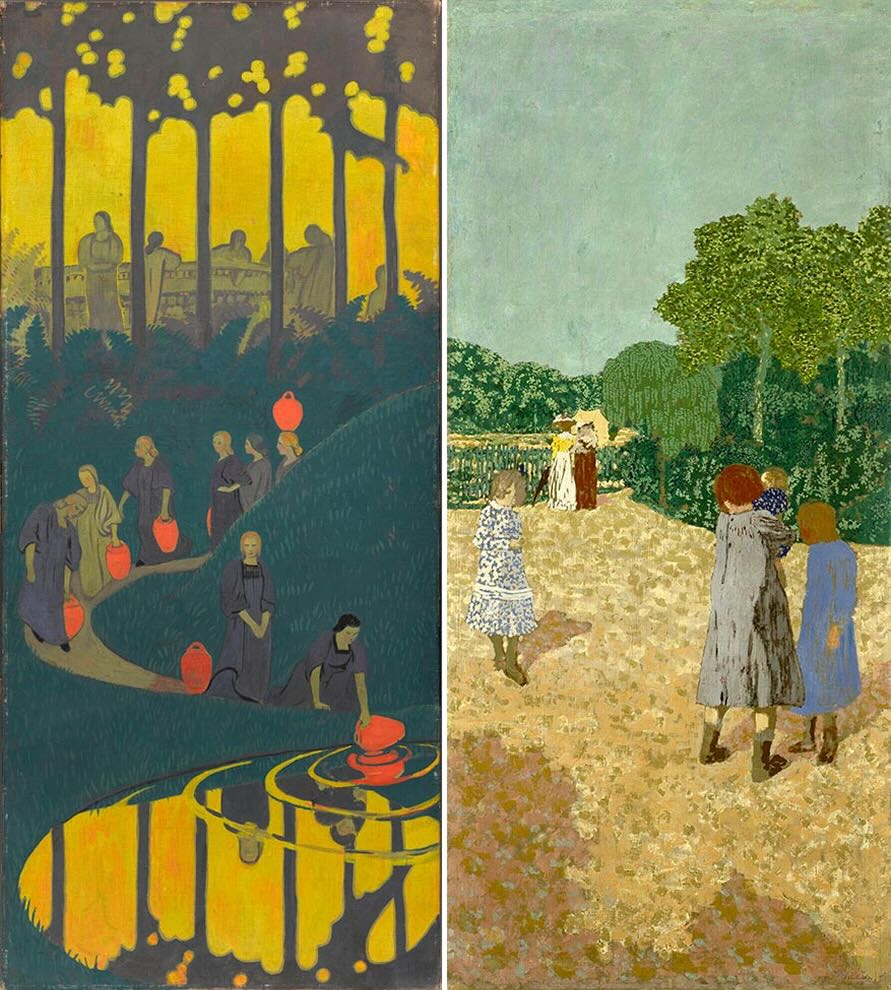

Subjects taken from modern life : Although close to symbolism, the Nabis were also interested in contemporary life, which they elevated to the rank of artistic subject.

Collective work and team spirit : United by bonds of friendship and a common vision, they consider themselves a “secret society” with their own rituals and vocabulary.

In summary, the Nabis movement is distinguished by its spiritual dimension, its decorative aesthetic, its desire to break down barriers between the arts and its commitment to a collective and innovative approach.

Birth of a movement

Carried by Brittany

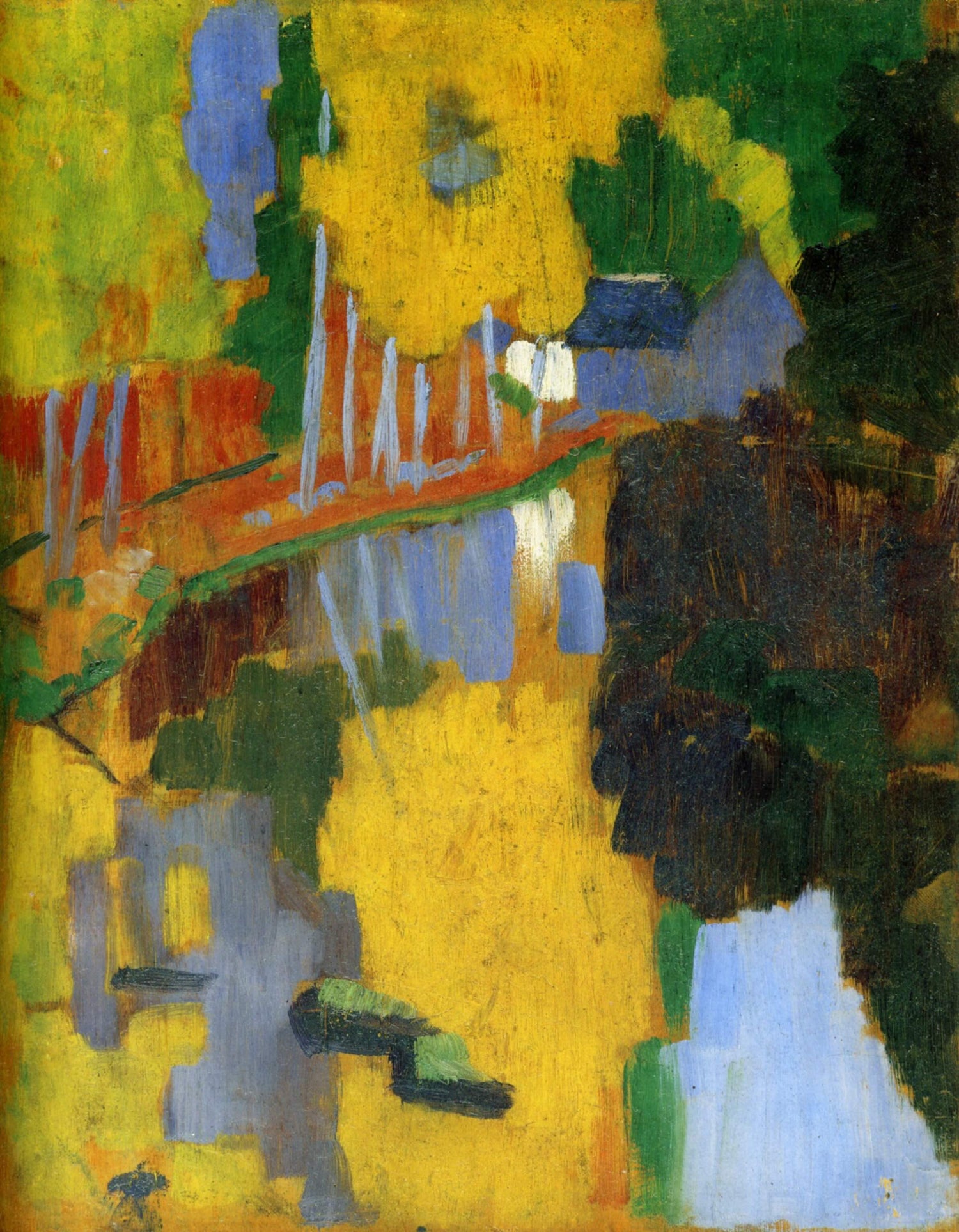

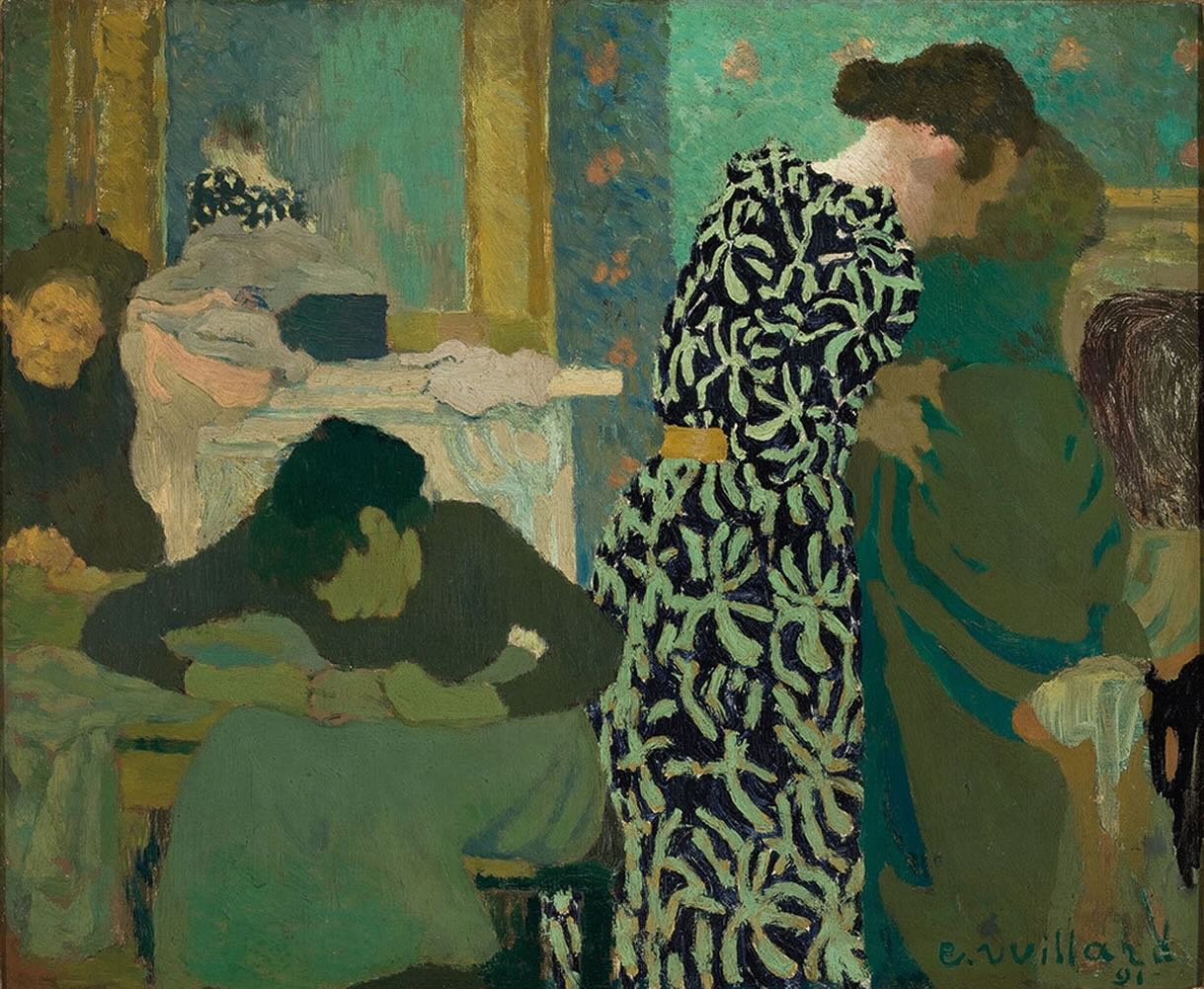

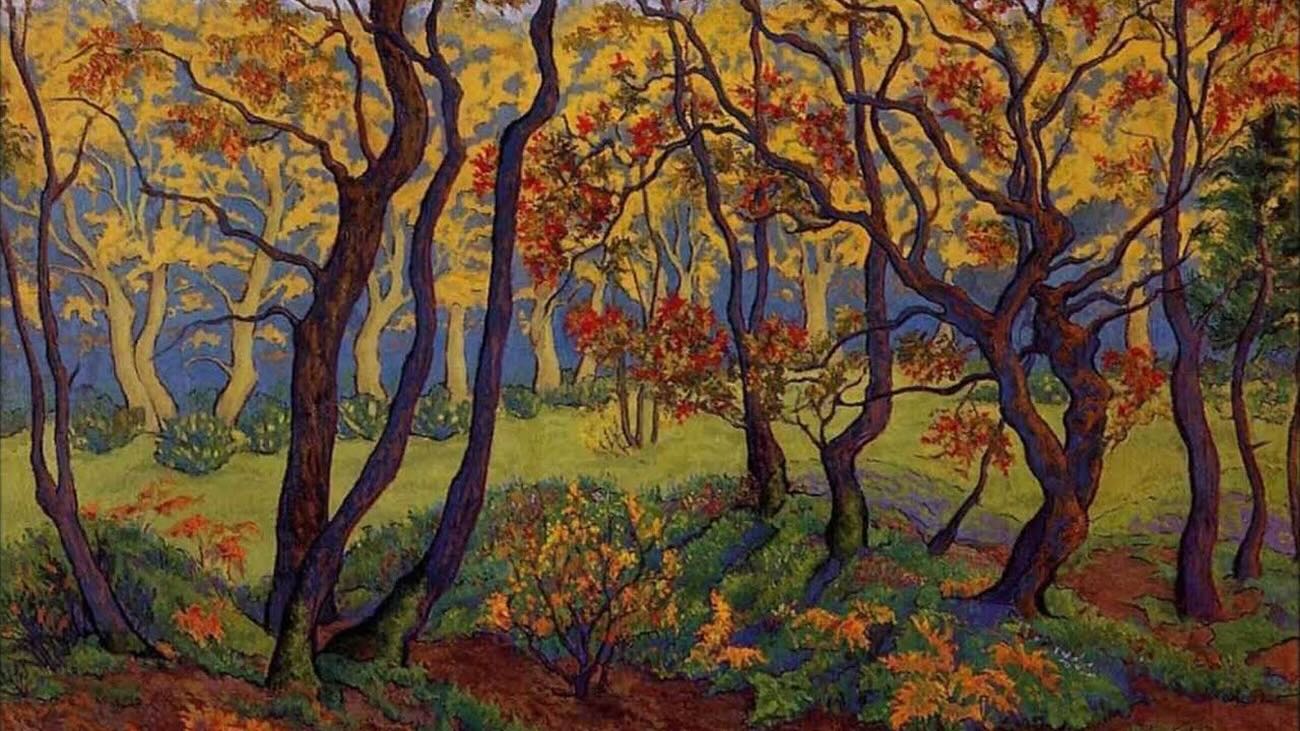

The Nabis movement emerged in the late 1880s around a group of young artists, mainly students at the Académie Julian in Paris, such as Paul Sérusier, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, Édouard Vuillard and Paul-Élie Ranson.

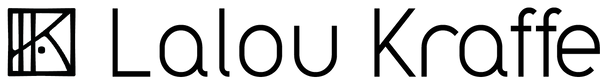

The trigger was Paul Sérusier's stay in Pont-Aven in the summer of 1888, where, under the direction of Paul Gauguin, he painted The Talisman.

This work, painted according to the principles of Gauguin's synthetism (flat areas of pure color, simplified forms, rejection of realism), became the group's manifesto.

Upon his return to Paris, Sérusier shared this experience and his painting with his comrades, who were enthusiastic about this new approach. The group then adopted the name "Nabis," a Hebrew term meaning "prophet" or "inspired," and adopted its own rituals and language, like a secret society.

Their common ambition is to renew painting by freeing itself from academicism, by favoring formal simplification, color and an ornamental and symbolic language.

spirituality

At the heart of the Nabi movement

Spirituality is essential in the artistic approach of the Nabis because it constitutes the very heart of their research and their expression.

For them, art is not simply a representation of the visible world, but a means of exploring and conveying inner realities, deep emotions and symbolic ideas.

The Nabis viewed artistic creation as a quest for the sacred, a way of going beyond materiality to reach higher levels of meaning and contemplation.

Their painting is thus intended to be a spiritual language, using color, form and symbols to evoke the invisible and invite the viewer to an introspective experience.

This approach makes the act of painting a truly meditative act, where the artist seeks to reveal the essence of the world and establish a link between the visible and the invisible.

Spirituality, among the Nabis, therefore allows art to become a space for reflection, elevation and sharing of a universal and timeless dimension.

Spiritual Quest

Expressing the invisible

The Nabis' spiritual quest profoundly transformed their artistic approach, making art a means of exploring and expressing the invisible, the sacred, and the interior.

Rather than limiting themselves to the simple representation of reality, they sought to translate emotions, ideas and universal truths through color, form and symbol.

Their creation thus becomes a meditative act, a kind of ritual where each work opens a window onto the soul, inviting the viewer to inner reflection and a contemplative experience.

This approach leads them to abolish the boundary between the profane and the sacred: the work of art becomes a space for dialogue with the divine, a mirror of the human spirit, and a guide to self-discovery.

By integrating spirituality into the heart of their creative process, the Nabis made painting a universal language, capable of connecting the artist, the work and the public around a common quest for meaning and elevation.

decorative arts

Beauty in our daily lives

The Nabis incorporated decorative art into their work, seeking to abolish the boundary between fine and applied arts, in order to introduce beauty into everyday life.

They used many decorative media: prints, posters, illustrations, show programs, wallpapers, screens, tapestries, stained glass windows, tableware and furniture.

Their approach is inspired by Japanese printmaking, which translates into simplified forms, soft lines, stylized patterns and an absence of traditional perspective, with bright colors and ornamental compositions.

The Nabis thus created decorations for private interiors, public commissions or everyday objects, affirming the decorative and accessible dimension of art.

Their approach, based on fantasy, poetry and experimentation, makes them true pioneers of modern decor, committed to a conception of total art, where all artistic disciplines come together to enrich the aesthetic experience of each individual.

Art life

Meaning, emotion and aesthetics.

The Nabis' decorative objects reflected their vision of art in relation to life by integrating beauty and poetry into everyday life.

For them, art should not be limited to easel paintings, but should invest all aspects of the domestic environment: screens, tapestries, wallpapers, stained glass windows, crockery, furniture, etc.

This approach aimed to abolish the boundary between art and life, by making each utilitarian object a work carrying meaning, emotion and aesthetics.

By creating decorative objects, the Nabis affirmed that art could transform everyday experience, awaken the senses, stimulate the imagination, and offer a space for contemplation, even in the simplest gestures of life.

Their approach defended the idea of a total art, accessible to all, where each element of the decor contributes to the development of the individual and the creation of a harmonious environment.

Thus, their decorative objects were the natural extension of their artistic quest: to make art a living experience, shared and fully integrated into existence.

A major contribution

The Nabis and the Pont Aven School

Technically, the Nabis movement profoundly renewed the painting of their time through several major innovations:

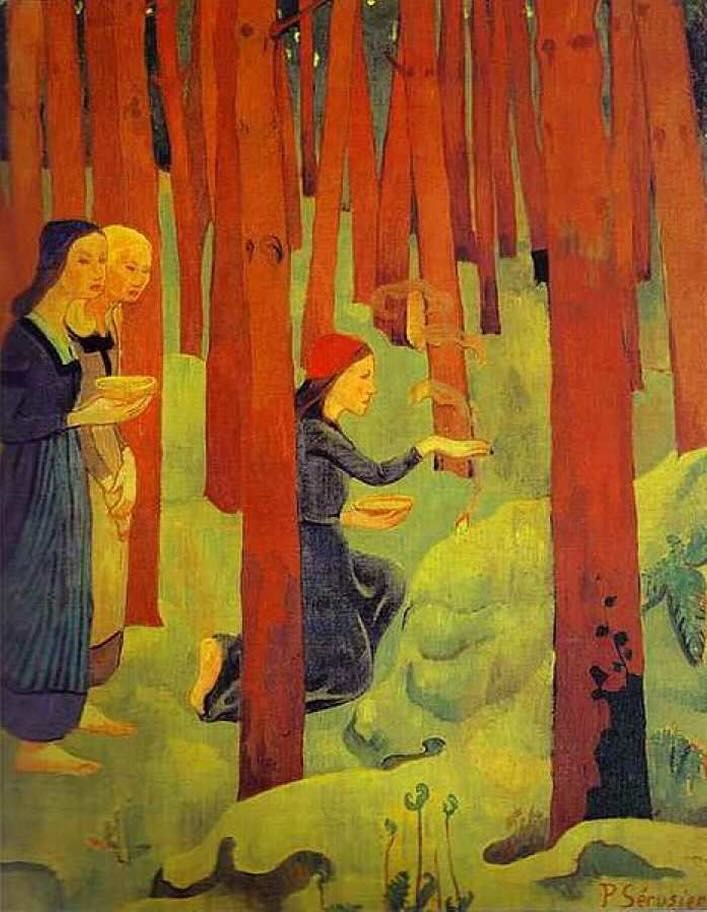

Simplification of forms : The Nabis abandoned realism and the faithful representation of nature in favor of refined, stylized forms, often inspired by Japanese art and ukiyo-e prints.

Pure color blocks : They use bold, unmixed colors, applied in blocks, which gives their works great visual intensity and a new decorative dimension.

Marked contours : Silhouettes and objects are often surrounded by sinuous and clear lines, accentuating the graphic and ornamental aspect of the composition.

Abandonment of traditional perspective : The Nabis rejected the depth and perspective inherited from the Renaissance, preferring flat compositions and formats inspired by the Japanese kakemono.

Integration of decorative motifs : Their paintings are characterized by the profusion of patterns, textures and decorative rhythms, which bring painting closer to applied arts and crafts.

Diversification of media and techniques : The Nabis painted on a variety of media (screens, fans, wallpapers, tapestries, stained glass, everyday objects), blurring the line between fine arts and decorative arts.

In summary, the Nabis transformed the painting of their time by making it more expressive, decorative and open to new media, while emphasizing color, the synthesis of forms and the abstraction of reality.